There are eerie similarities between today and the forgettable 1970s. Will history repeat itself, making 2020s the new 1970s?

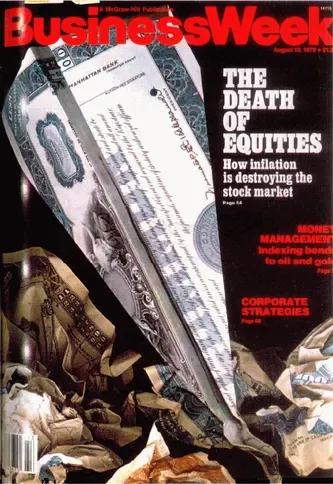

In 1979, the BusinessWeek, a popular American weekly, ran a cover story titled “The Death of Equities– How Inflation is destroying the stock market”. The story was timely– US equities had earned zero return for investors for more than ten years. The mood of equity investors was sombre, and if they were looking for solace, the above-mentioned cover story would have provided none.

The 1970s was a decade of high inflation, rising interest rates and disturbing geo-political events. Fast forward fifty years to today, and the same environment is staring down at us. History has a bad habit of repeating itself and if the next few years are anything like the 1970s, we should brace ourselves.

Revisiting the 1970s

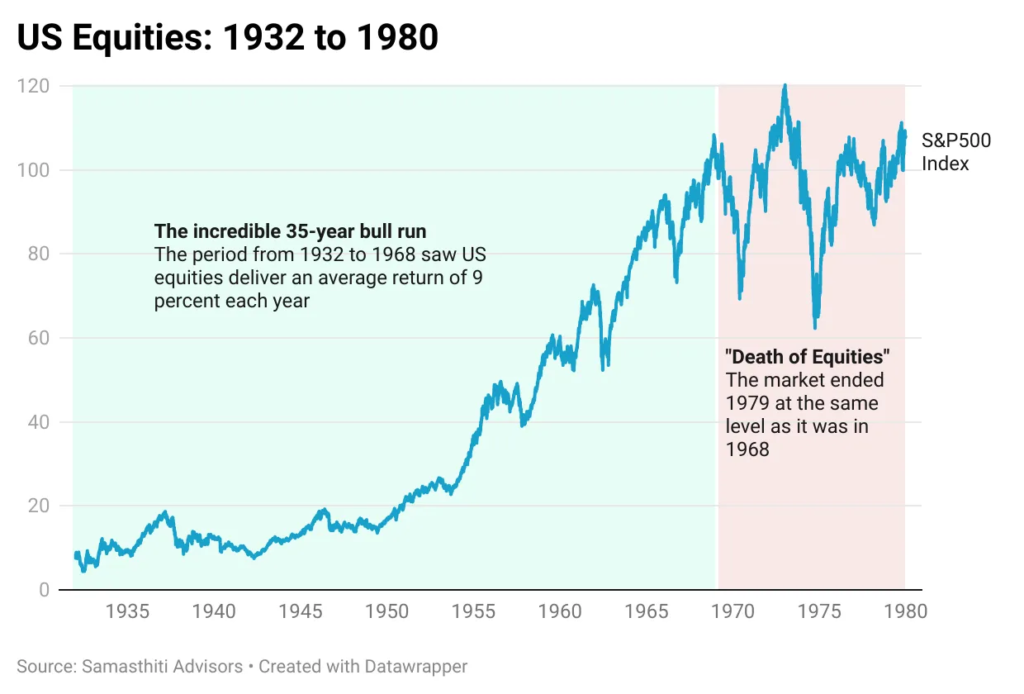

For about 35 years, from the year 1932 to 1968, US equities had delivered an impressive average return of 9 percent each year. The good times brought with them a massive increase in the number of investors investing in equities. Between 1948 to 1968, investors in equity increased by 2.5 times in the US.

After this stupendous performance, came the downfall. Between 1968 and 1974, the US equity market fell 30 percent. Post that, the markets staged a comeback, but only managed to climb back to the level they were at in 1968. Thus, for the period from 1968 to 1979, the US equity markets delivered zero returns.

You must have heard the annoying advice– invest for the long term. Well, here we have an example of an investor investing in equities for more than 10 years and earning no returns. What would have been even more painful for the American investor is that while equity returns remained flat, inflation was running high, eating away their money’s purchasing power. Double whammy!

By any standards, the 1970s was a tumultuous period. High inflation, low economic growth, oil-shocks and geo-political risks– all combined to create the perfect storm.

The average inflation in the US during the 1960s was 2.3 percent. By the end of 1979, inflation had sky-rocketed to 13.3 percent. The Federal Reserve (the American central bank) faced a severe lack of credibility due to its inability to rein in inflation. It had become conventional wisdom that high prices had gotten entrenched– inflation was now structural.

More worrisome was the fact that high inflation was not accompanied by high growth. This phenomenon required the coining of a new term called “stagflation”– a combination of stagnation and inflation.

One of the causes of high inflation was the oil price shock in the year 1973. In that year, US President Nixon took steps to provide emergency aid to Israel in its war against the Arab nations (popularly known as the Yom Kipuur War). In retaliation, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced an oil embargo on the US. Following the embargo, imported oil price in the US jumped nearly four times from about USD 3 per barrel to USD 12 per barrel.

If this was not enough, there was a second oil price shock. In 1978, the Iranian Revolution led to a fall in oil production of about 4.8 million barrels per day. This constituted 7 percent of the global oil production at that time. This fall in production, coupled with fears of more supply disruption, led to a doubling of oil prices between 1979 and 1980.

The events during the 1970s were clearly not encouraging. Close to 7 million investors left equity investing during that decade. Due to the terrible performance of equities, investors started diversifying their investments into commodities and real estate. Several large investors in the US started investing in property, gold, silver and diamonds.

The dominance of equity investments had come to an end. You could argue whether equities were indeed dead, but there was no doubt that it was in ICU.

The parallels between today and the 1970s

Will the 2020s become the new 1970s? We can’t be sure, but there are eerie similarities.

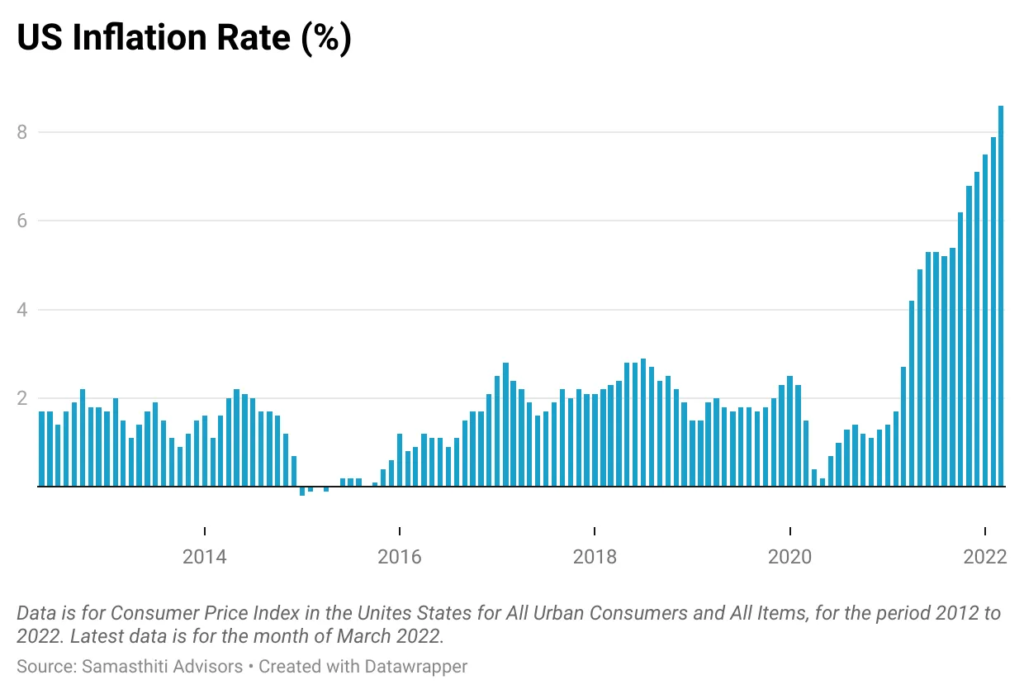

First, after a sustained period of low inflation, the US is now moving to a higher inflation regime. For the period 2010 to 2020, inflation in the US averaged 1.7 percent each year. The latest inflation reading for March 2022 is 8.6 percent – a forty year high. There are obvious parallels here. Inflation averaged 2 percent between 1960 and 1968, and then started inching up in the next couple of years before breaching 10 percent in 1974.

Second, interest rates have started to increase. After keeping interest rates at close to zero percent to fight the Covid induced economic slowdown, the Federal Reserve increased interest rates in the US by 0.5 percent on May 4, 2022– the biggest single hike in two decades. This is expected to be one amongst a series of interest rate hikes to tackle inflation.

If we rewind the clock, this pattern seems familiar. For the period 1960 to 1967, interest rates in the US averaged 3.5 percent. From 1968 onwards, interest rates were gradually increased to combat inflation, and rates finally reached a high of 13 percent in 1974.

Third, reminiscent of the 1970s, geo-political events and the accompanying supply side shocks are leading to an increase in the price of oil and other commodities. The Russia-Ukraine war has led to oil prices doubling from about USD 50 a barrel a year ago to about USD 110 a barrel now. Apart from oil, prices have increased for other commodities as well due to supply disruptions.

Fourth, equity markets are correcting after a fantastic run– just like in the 1970s. Between 2009 to 2021, US equities, as measured by the return on the S&P500 Index, delivered an impressive average return of 13 percent each year. Since the start of 2022 however, the mood has soured significantly, with the market down 20 percent.

So, the ingredients are there to make 2020s the new 1970s. However, it is much too early in the cycle to be sure. Whether it is inflation, interest rates or the fall in equities– the trends are similar, but we will need to see if they persist.

Do we need to fear?

Even if the 2020s does turn out to be like the 1970s, for those willing to wait out the winter, the spring awaits – and what a lovely spring a long winter brings.

The BusinessWeek cover on the “Death of Equities” was released on August 13, 1979. After being ravaged by the first oil shock, the second oil shock had come knocking in that year. Interest rates climbed even higher than the high of 13 percent in 1974. Inflation, after moderating a bit to 7.6 percent in the previous year, escalated to 11.2 percent in 1979.

The cover story was hardly radical – it was announcing what already seemed obvious. It was an obituary to an already dead equity market. However, like it is the darkest before dawn, the year 1979, unbeknownst to all, turned out to be the harbinger of a bright morning- so bright that you had to squint your eyes.

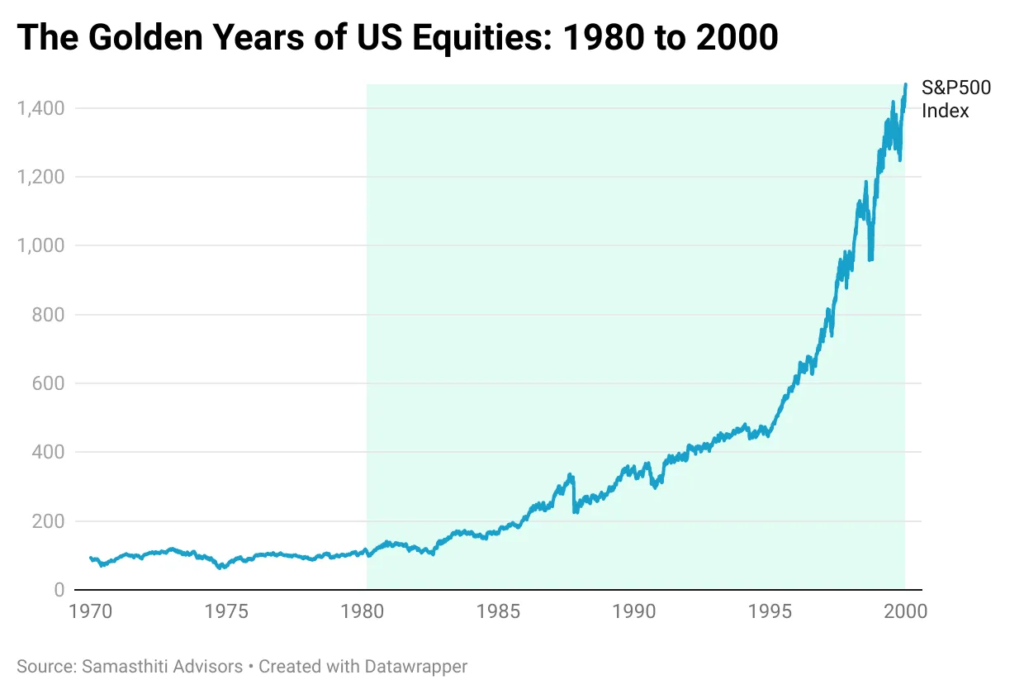

From the date of publication of the BusinessWeek cover story, to about a year later, investors were rewarded with a 30 percent rally in equities. But this was just the trailer. The next 40 years would go down as the golden period of American equities. From 1980 to 2000, US equities returned an average of 14 percent each year. Clearly, it was catch up time.

You must have heard the annoying advice– invest for the long term. Does it still sound so annoying?

0 Comments