(A condensed version of this post was published in Mint on 13th July 2025 and can be accessed here https://www.livemint.com/money/personal-finance/retirement-fund-planning-equity-alloation-debt-allocation-bucket-strategies-sequence-risk-withdrawal-rates-rebalancing-11752389550763.html )

In a previous write-up titled “Why More Equity May Hurt Your Retirement Portfolio,” we demonstrated that increasing equity exposure beyond a certain point actually lowers safe withdrawal rates. This sparked considerable debate and criticism. Many argued that a bucket strategy—which segments assets into different time horizons and allows short-term withdrawals to come from conservative assets—could allow retirees to hold higher equity allocations without increasing risk.

In this follow-up, we examine why this is not the case.

The key criticism we received

The main criticism directed at our earlier analysis was that it assumed uniform, pro-rata withdrawals across asset classes, without recognizing how bucket strategies isolate volatile assets (like equity) from short-term spending needs. Critics suggested that by drawing only from debt and allowing equity to recover after downturns, retirees could maintain higher equity allocations without the adverse effects of early losses. The assumption was that this approach effectively neutralizes sequence risk.

But does it really?

An important clarification is in order here

In our earlier analysis, we were not doing pro-rata withdrawals at all. In fact, we were withdrawing solely from the debt portion of the portfolio. In other words, our earlier analysis already had similarities with a bucket strategy. There were no withdrawals being done from equity in down markets, and the debt allocation acted as a reserve for recurring expenses.

The key difference between our analysis and bucket strategy

While our earlier analysis shares similarities with a bucket strategy, there is a key difference. Our previous analysis used a monthly portfolio rebalancing, whereas in a bucket strategy, there are decision rules regarding when to rebalance. Typically, rebalancing in a bucket strategy is done when the equity portfolio is sitting on gains.

To test whether the decision rule-based rebalancing of a bucket strategy is superior to simple periodic rebalancing that we used in our analysis, we compared the safe withdrawal rates obtained under both methods.

Testing a bucket strategy

We simulated a classic bucket strategy with the following rules:

- Start with a given equity–debt mix.

- Withdrawals are made from the debt portion.

- Rebalancing occurs when 12-month rolling equity returns exceed 10%, i.e., when markets have done well and there are capital gains to harvest.

This configuration prevents booking equity losses and mimics the common advice in bucket strategies – “don’t sell equities in a downturn.”

We compared this with our disciplined periodic monthly rebalancing strategy (from the previous study) across various equity allocations. The graph below summarizes the maximum safe withdrawal rate achievable under both approaches for each equity allocation.

Bucket strategies underperform

As is evident from the data, the safe withdrawal rates obtained under the bucket strategy are lower than for the periodic rebalancing method. This is not surprising at all—definitely not for those familiar with retirement planning.

Simple periodic rebalancing strategies outperform bucket strategies because they not only avoid selling equity at market bottoms but also actively buy equity when valuations are low. This is a critical strength that traditional bucket strategies fail to exploit.

Illustration

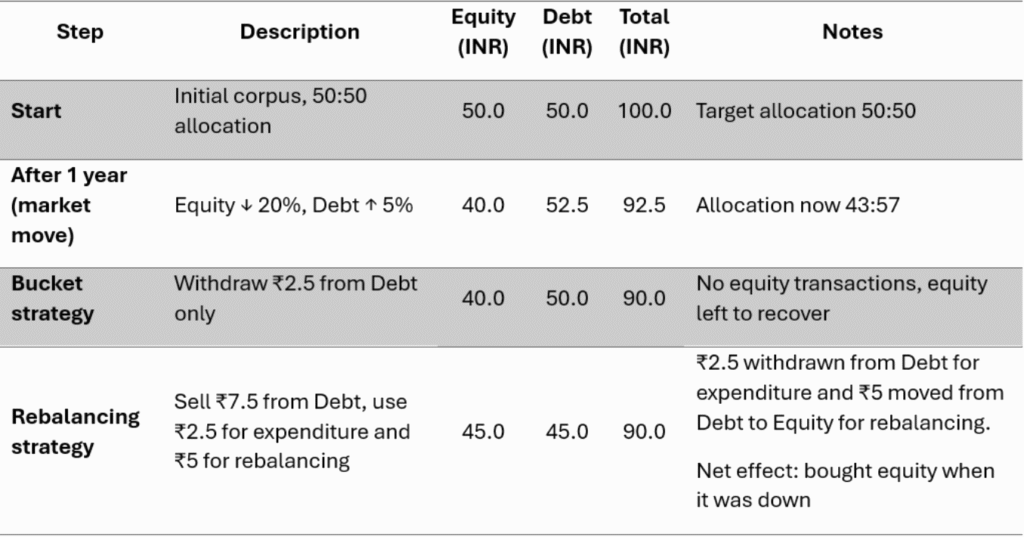

Let’s say someone has INR 100 as retirement corpus and is running a 50:50 equity: debt strategy. After a year, equity has fallen by 20%, while debt return is 5%. The new balance is INR 40 (equity) and INR 52.5 (debt). If you need a withdrawal of, say, INR 2.5 for expenses, you will withdraw the same from debt, letting equity recover.

Now let’s compare this to a plain-vanilla rebalancing strategy (what we used in our earlier analysis). After a year, the equity balance is INR 40, and the debt balance is INR 52.5, so the equity: debt ratio is 43:57, which has deviated from the target of 50:50. So, you will sell debt and rebalance to equity. You sell INR 7.5 from debt, from that you can use INR 2.5 for withdrawals, and the balance INR 5 is used to buy equity. Now, your equity and debt balance is INR 45 each, and you are back to the 50:50 equity: debt allocation.

As you can see, even without a bucket strategy, there is no selling from equity that takes place. Rebalancing itself ensures that we don’t sell equity when markets are down – buckets don’t matter. In fact, you are buying equity when markets are down (which does not happen in a typical bucket strategy), which is why we are able to get better outcomes in a simple, boring rebalancing strategy as compared to buckets.

Rebalancing in bucket strategies is a one-way street. You rebalance from equity to debt when the equity portfolio is sitting on gains. You miss out on the reverse, which is rebalancing from debt to equity when equity is down, which happens automatically in a periodic rebalancing strategy.

If you are now going to argue that we can implement a two-way rebalancing between equity and debt in a bucket strategy as well, then it will no longer remain a bucket strategy but will morph into a periodic rebalancing strategy!

If the goal is to avoid selling equity in downturns, that can be achieved more elegantly—and efficiently—by following a rule-based rebalancing approach, with withdrawals targeted from debt or low-volatility assets. A well-rebalanced portfolio already does most of what buckets claim to do—and often, better.

The reason you may want to use a bucket strategy is not because it has an edge in delivering higher withdrawals, but because it can provide emotional comfort. Retirees often engage in mental accounting and view their savings as separate “buckets” for near-term and long-term needs. This can reduce panic during equity drawdowns.

However, using a bucket strategy under the illusion that it reduces sequence risk—and therefore justifies a higher equity allocation—can be misleading, if not outright dangerous. Don’t just take my word for it. Harold Evensky, widely regarded as the “Father of the Bucket Strategy”, has been clear that the bucket approach is not a tool for boosting returns, but rather a form of behavioral insurance designed to help investors sleep better at night, not retire richer.

Bucket Strategy is a psychological hack! It makes one feel fuzzy and warm but at a cost. The cost is lower WR. If one can extend working life or reduce expenses to get the multiple from 25x to 30x go ahead and start bucketing. Otherwise all simulations show Bucketing leads to higher failure rates.