(A condensed version of the below article was published in Mint on June 1, 2025, and can be accessed from the link below.)

Why History Misleads Indian Retirees

How much can an Indian retiree safely withdraw each year without running out of money? In developed markets, the answer comes from long historical data. In India, history is a poor guide — not just because our financial markets are young and data is limited, but also because asset returns have seen a steady decline.

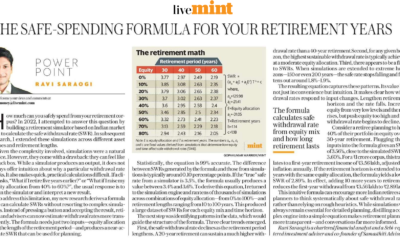

In markets such as the United States, financial data spans more than a century, offering an excellent foundation for empirical analysis. William Bengen used this long record to conduct his seminal study on safe withdrawal rates. Using rolling 30-year retirement periods, Bengen demonstrated that an initial withdrawal rate of 4%—subsequently adjusted for inflation—would have sustained a retirement portfolio through all historical scenarios. This finding became the famous “4% rule”.

In India, data is far more limited. The country’s oldest equity index, the Sensex, has data from 1979, yielding only a 45-year history. This is short, given that a typical retirement horizon spans three decades.

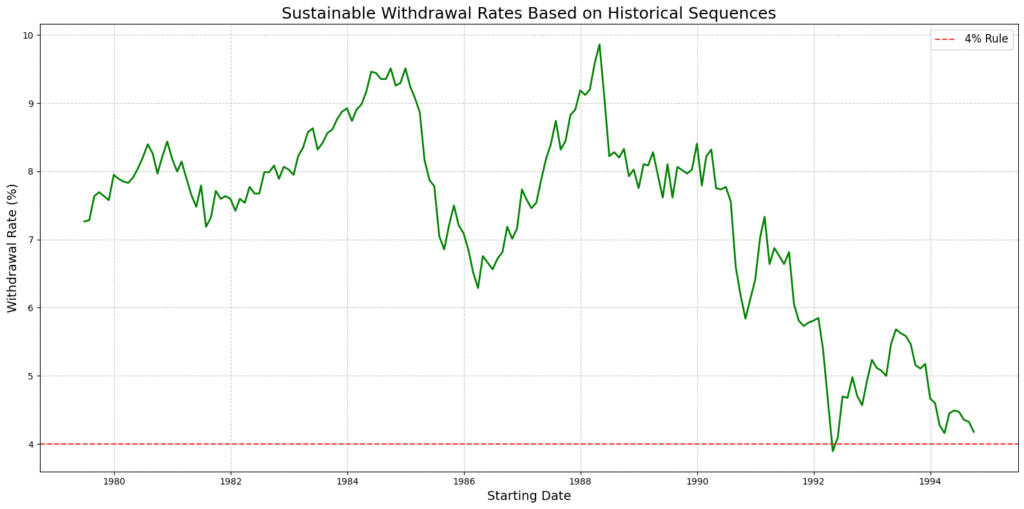

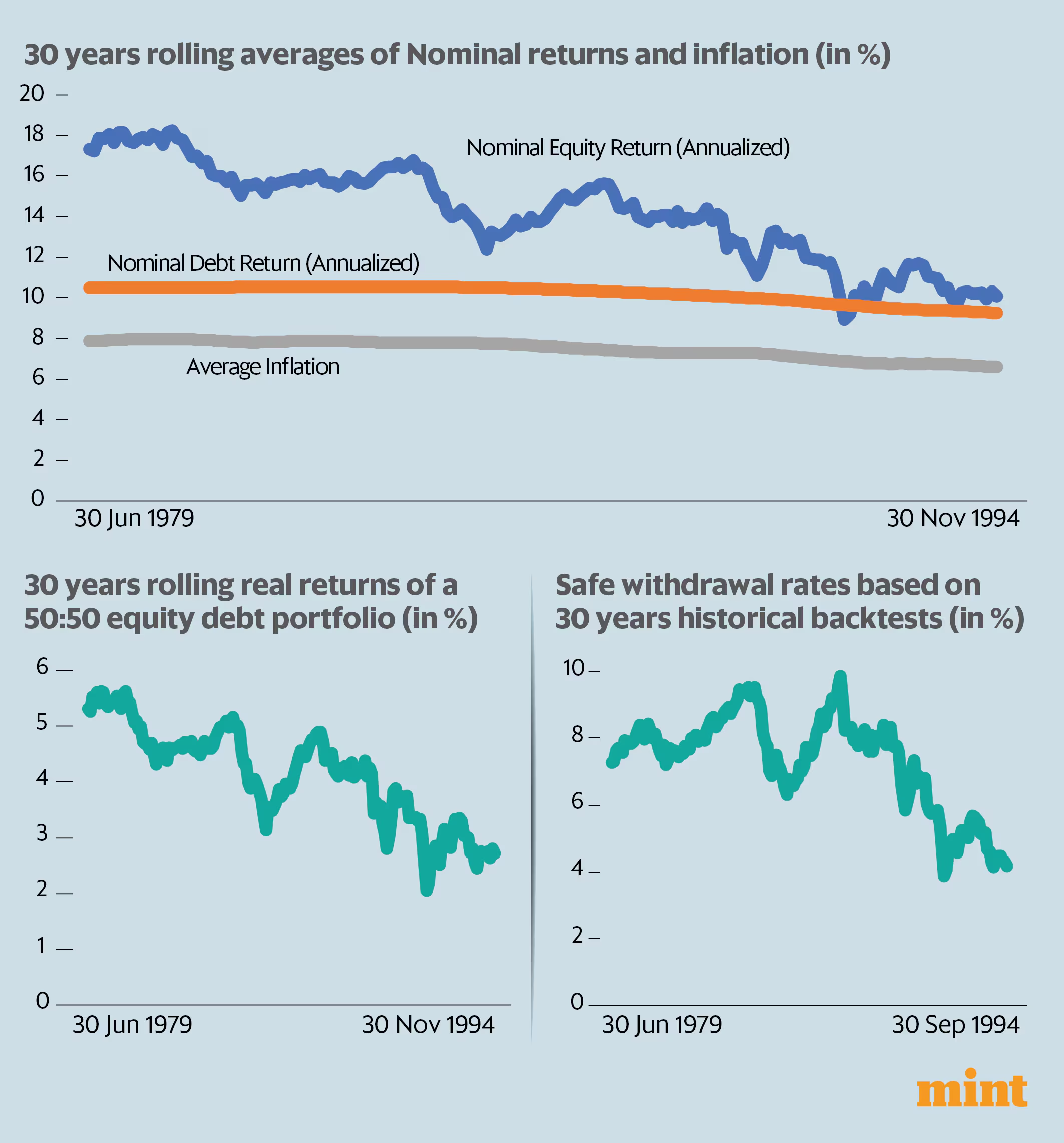

Nonetheless, we examined all available rolling 30-year periods beginning in June 1979. The first window spans June 1979 to May 2009, the next July 1979 to June 2009, and so forth. For each period, we calculated the safe withdrawal rate—the highest inflation-adjusted annual withdrawal that would not deplete the portfolio over the retirement term.

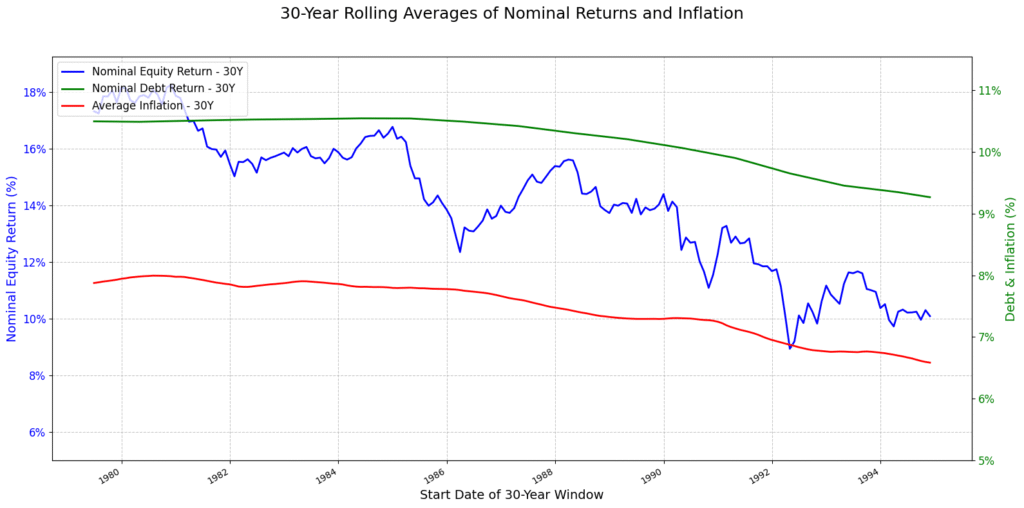

Historical data show safe withdrawal rates above 4% in nearly all the 30-year periods. But that does not mean future withdrawals can be as generous. Asset returns in India have steadily declined. Since equity and debt returns are lower today than in the past, back-tests may not only fail to predict future outcomes—they may systematically mislead.

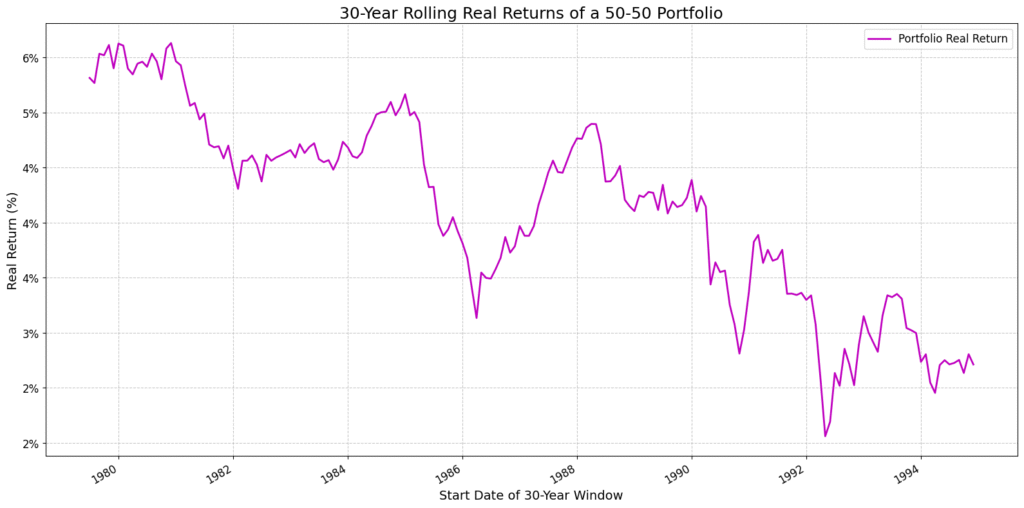

It is no solace that the decline in asset returns has been accompanied by declining inflation. The fall in inflation has not been adequate to keep real returns stable. Real returns on a typical balanced portfolio have steadily declined. Future retirees are unlikely to experience the same portfolio performance as previous generations.

When historical data exhibits a pronounced trend—whether upward or downward—relying solely on back-tests can be misleading. In such cases, methods like Monte Carlo simulations offer a more robust framework. By generating thousands of synthetic scenarios based on a range of assumptions, these simulations account for uncertainty in future returns more effectively than historical extrapolation.

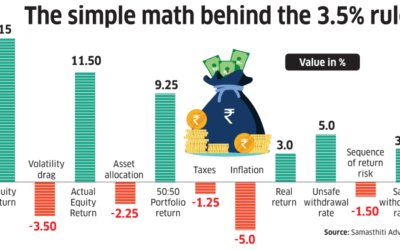

My 2022 study on withdrawal rates for India, which used Monte Carlo simulations, found that the commonly cited 4% rule was too optimistic. A 4% withdrawal led to premature exhaustion of a retirement portfolio in about a third of the scenarios, while a 3% rate reduced that risk sharply. In a subsequent 2024 co-authored study with Rajan Raju, we used similar techniques to estimate that a withdrawal rate of 3–3.5% was more appropriate for Indian retirees.

In developed markets, a long history makes the past a useful guide. In India, history is shorter—and kinder than it should be. Retirees must rely less on what was and more on what might be. Caution, not nostalgia, demands a lower safe withdrawal rate.

-Ravi Saraogi, CFA — SEBI Registered Investment Adviser and co-founder, Samasthiti Advisors.

0 Comments